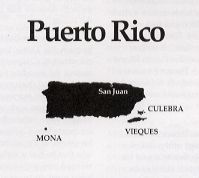

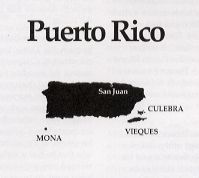

Puerto Rico has commonwealth status today (1998). This status has the following characteristics:

-

Puerto Ricans are citizens of the United States and can travel freely within U.S. territory.

-

Puerto Rico has its own constitution. The Puerto Rican government has control over most domestic affairs, but not foreign affairs. The United States regulates Puerto Rico's contact with other countries.

-

Puerto Ricans living in Puerto Rico cannot vote for the president of the United States.

-

If the draft were reinstated, Puerto Ricans could be drafted into the U.S. military.

-

Puerto Rico sends one nonvoting representative to the U.S. Congress.

-

The Puerto Rican governor and the members of the Puerto Rican House and Senate are elected by popular vote.

-

The United States can control the use of the Puerto Rican National Guard.

-

U.S. environmental laws apply to Puerto Rico. However, they are not enforced as strictly in Puerto Rico as they are in the United States.

-

The United States controls Puerto Rico's postal and immigration regulations.

-

Puerto Ricans do not pay federal taxes, although they do pay taxes to the commonwealth government.

-

The United States provides for Puerto Rico's defense.

-

The U.S. military uses Puerto Rico as a base in the Caribbean and as a military testing site for weapons.

|

If Puerto Rico became a state of the United States, it would have the following characteristics:

-

All Puerto Ricans would be U.S. citizens, with the right to travel freely throughout U.S. territory.

-

In time, Puerto Rico would most likely lose a sense of being its own country. Only the U.S. flag and national anthem would be honored. Schools would teach U.S. history and culture even more than they do today.

-

People living in the state of Puerto Rico would vote in all federal elections (including for president of the United States). Puerto Rico would have a state constitution, and representatives would be elected to a state legislature.

-

If the draft were reinstated, Puerto Ricans could be drafted into the U.S. military.

-

The state of Puerto Rico would have voting representatives in both houses of the U.S. Congress.

-

The state of Puerto Rico would have a governor like all other states in the United States.

-

The federal government would control the use of Puerto Rico's National Guard, as it does with all states.

-

Puerto Rican state laws plus U.S. federal environmental laws would protect the environment.

-

All U.S. federal regulations would also apply to the state of Puerto Rico.

-

Puerto Ricans would pay federal taxes, as well as state and local taxes.

-

The United States would provide for the defense of Puerto Rico, as it does for all states in the United States.

-

The U.S. military could continue to use Puerto Rico as a base in the Caribbean and as a military testing site for weapons.

|

If Puerto Rico became independent, it would be a sovereign nation, with the same control of its own affairs as any country. It would have the following characteristics:

-

Citizens of both Puerto Rico and the United States would no longer automatically have the right to travel between the two countries. They would be subject to the immigration laws of both countries.

-

Puerto Rico would have its own constitution with control over domestic and foreign affairs. For example, Puerto Rico might be free to do more trading with countries other than the United States.

-

Puerto Ricans living in Puerto Rico would no longer be citizens of the United States. They would not vote in U.S. elections, but in their own elections.

-

Puerto Rico would have its own government, including representative bodies and elected officials.

-

Puerto Rico would elect a president with more power than the current governor. The House and Senate, or their equivalents, would have more power than the current Puerto Rican House and Senate.

-

The Puerto Rican National Guard would no longer be controlled by the U.S. government.

-

Puerto Rico would make and enforce its own laws to protect the environment.

-

Puerto Rico would develop its own postal and immigration regulations.

-

Puerto Ricans would pay taxes to their own government.

-

Puerto Rico would have to develop its own military defense.

-

The U.S. military would no longer be able to use Puerto Rico as a base in the Caribbean and as a military testing site for weapons, unless a special agreement were negotiated between the two countries.

|